|

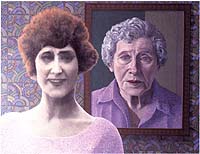

My Mother at 18 and 88 347 x 450 pixels, 43 Kb

The Artist's Mother 420 x 400 pixels, 62 Kb

The Artist's Mother 379 x 450 pixels, 45 Kb

The Artist's Mother 274 x 200 pixels, 19 Kb

|

My Mother at 18 and 88 No photograph survives of my mother as a very young woman except a tattered snapshot taken by her then boyfriend Maurice Price. It is in part to his failure finally to win my mother's hand that I owe my existence. The foreground face in this picture is based on this image which blurredly records a daring weekend by the sea the two young lovers took in 1919. Needless to say they slept in separate rooms. My mother always remembered the episode with a sigh which somehow incorporated a might-have-been and a perhaps-just-as-well. On the wall just behind is a picture of her painted direct from life at the age of 88. She used to come on Saturdays to the studio for lunch and drawing or painting her became part of the afternoon ritual. Both this picture of my mother as an old lady and the picture as a whole were done at 57 Talfourd Road in Peckham (where I still work) a house that was very much part of our history. She had bought it as an investment for £500 in the fifties in order to rescue the family finances from my father's more risky business ventures. She let it to students at Camberwell School of Art. When I in my turn ten years or so later went to that art school I lived there myself. As lodgers left I look over the rooms and eventually occupied the whole house. As is the way with art the picture is almost the opposite of what was intended. My original scheme had been to have the young Margaret Agnes Arnold in a frame on the wall of the studio and to paint the long widowed Mrs Phillips sitting in front of it: an aged woman with background memories of her youthful remembered self, an event real in time and space. Somehow although I had started on the painting in this way I felt a strong reaction against the standard trope of age musing on ever retreating youth. Old age, after all, no more nor less includes our former selves than youth contains the inevitability of our selves to come. That is why both ends of the time spectrum have their poignancy. As a pictorial problem the flat image on the wall asserting the roundedness of the painting from life made the whole thing too easy a portraitist's trick (I do not ever think of myself as a portrait painter). Nor did this strategy accord with my mother's character. She was a great liver in the present and was always interested in what was going to happen in her family and in the world. Anyone who has lived even for a few decades faces the inescapable irony that the inner self is constantly fixed in youth and exists in a continuous adventure of the present. The shock of the mirror telling us that this ever youthful soul is the prisoner of an ageing face and body can take us by sad surprise. Thus bit by bit the two versions of my mother changed places. The real person was the young girl and the changes wrought by time became the unreal truth. It was a battle to wrest from a shakily taken and fumblingly developed black & white snapshot any kind of presence that would command the pictorial situation. My mother was able to dictate certain details like the colour of her hair and dress. The studio itself soon disappeared in favour of a fictional wall of memory with a wallpaper based on recollections of the decorative boxes that my mother used for her cosmetics and that she had kept from before her marriage (my father manufactured perfumes and it was in his factory that my mother had been employed). These were amongst my first objects of visual fascination and, I guess, had an art deco origin. However I flattened the image from life it always looked more present than the elusive figure of the photograph. This gave the painting an odd tension, a satisfyingly disturbing oddness. My mother was a patient sitter and was always intrigued by the picture as it went on. She invariably (and correctly) described it as 'most peculiar'. Nonetheless she was proud to see it hanging in my exhibition in the National Portrait Gallery the year before she died and would have been even prouder to know that it has now found such a fine and famous home. The Ashmolean (No. 38 / Spring 2000), p. 21-22. The Portrait Works (1989), p. 13, 81, 84, 99. See also > > Essay: The Artist's Mother by Margaret Agnes Phillips

|