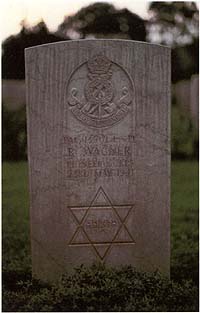

The British Cemetery, Crete, 1987

Photograph by Tom Phillips

301 x 450 pixels, 37 Kb

502 x 750 pixels, 71 Kb

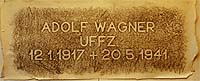

Inscription from German Cemetery, Crete, 1987

Rubbing by Tom Phillips

181 x 450 pixels, 36 Kb

302 x 750 pixels, 81 Kb

Gravestone in British Cemetery, Crete, 1987

Photograph by Tom Phillips

I gobbled up the background literature, mainly popular accounts written by Englishmen (Ill Met by Moonlight), Germans (Wings over Crete) and Cretans (The Cretan Runner) and spent a couple of days in the Museum's own library.

Whenever I asked anyone about Crete they came up with the name of John Craxton as the genius loci in terms that made him sound like a character in search of a Somerset Maugham story; the Golden Boy of British Art turned Gauguin of the Aegean. I had known his work since schooldays from illustrated books and magazines like New Writing. I wrote to him asking if I might have lunch with him when I got to Crete. It turned out that he knew something of my work too and in his unexpectedly warm reply, the tentative lunch date turned into an invitation to stay in Xania and a promise to show me the appropriate sites and sights.

John Craxton was more than good as his word and in company with him and his friend Nick Moore, I saw everything and met everyone it was possible to see and meet, including Patrick Leigh-Fermor and others whose story was told in Ill Met by Moonlight like the author/hero of The Cretan Runner, George Psychoundakis.

I have always liked cemeteries and the two huge graveyards, so dramatically sited, of those who fought in the Battle of Crete were places I returned to later on my own.

The German cemetery was, ironically, tended by George Psychoundakis himself, who, as a resistance fighter must have helped speed many of its residents to his later care: he now happily serves coffee to their relatives in the adjacent German Memorial Gardens Café. I wandered among the flat grey slabs reading names, noting down those that struck me, such as the namesakes of artists (Hans Hartung) or romantic sounding aristocratic air aces (Udo Von Haldenwang). Then, more systematically, I went along the rows reading each one of the thousands of mostly prosaic names (Heinrich Mayer, Ernst Haller, Ludwig Geiger...). Suddenly one particular name stood out from the others, an onomastic oxymoron of soaring squalor; ADOLF WAGNER. He had been twenty years old when I was born and was killed four days before my fourth birthday. I noted down the name among the others in my sketchbook and underlined it twice.

As I walked the ranks of tombs I could hear all the time the sound of marching feet and distant drill commands. There below me on the wartime airfield of Maleme, new young soldiers were training.

The British Cemetery (no café, but more lush and green with proper tombstones in golden Portland Stone) overlooks a site equally central to the battle of Crete, Suda Bay, now a base for the NATO fleet. Here I performed the same ritual, walking along the files of upright stones (all at attention for ever now) as if inspecting the troops. Without distinction of class or rank they stood in alphabetical array, their names formally cited; no 'Biffy' Hederson here nor 'Shorty' Long, as in the books. Now and then an unexpectedly exotic group of syllables announced a Maori who no doubt came to the island (as part of the New Zealand force) baffled as to where he was and for whom or what he played out this all too brief confused and savage rite. Once again it was nearly the last of the many thousand names that stopped me short...not a cross but the Star of David was carved beneath the name R. WAGNER who had been killed three days after Adolf. A jew called R. Wagner; could it be...? I hastened to the registry in the chapel and looked him up: his name was Richard. I instinctively knew that the conjunction of these two Wagners, plucked from the separated cemeteries where fate and enmity had cast them, each far from home and profitlessly killed in the same week fifty years ago, must prove the centre of my task. If I could make a union of their enforced antagonism it might bring about some minute symbolic healing of the wound of war, and, in this case, the more terrifyingly inoperable wound of racial hatred. I did not yet know how to do this and it took me some time back in England to work out how, with loss neither of reverence or resonance I might bring together those whom God had put asunder. > >